History shows that apathy is the final frontier before anarchy sets in. Pakistan is hurtling towards anarchy on many fronts, which is directly affecting our social, political and economic well-being.

One such front is the water calamity that is descending upon us. From the mighty ranges of the Himalayas to the coastlines of the Arabian Sea, the water crisis in Pakistan has reached a critical stage. It is much worse than the energy crisis, which will seem like a child’s play when compared to the water predicament. On the one hand, the awam is crying out loud in pain or silently suffering due to hopelessness while on the other, this same awam is in a lynching, attacking and destroying mood. Yet the movers and shakers of Pakistan continue to display that very Pakistani of traits: dekha jai ga.

Water protests have recently erupted in Karachi, Hyderabad, Khairpur, Jacobabad, Sukkur, Dadu, Quetta, Multan, Faisalabad, Lahore, Rawalpindi, Abbottabad and Peshawar. That is more than 50 percent of our population up in arms against water shortages and the cost of water. Farmers are protesting elsewhere. And what has the government done in response? Zilch. This is apathy at its peak.

Thousands of Pakistani children continue to die every year due to unsafe water and poor sanitation. Entire Pakistani cities are drinking contaminated water. Pakistan is already a water-scarce country (with insufficient water supply to meet the daily needs of its citizens) and is nose-diving into a water-starved status (drought like conditions). A month ago, Pakistan’s dams held water for only a few days and Irsa had to cut the share of all provinces.

Currently, the amount of water that Pakistan can store for emergency use is 30 days as compared to the international standard of 120 days. Pakistan’s economy is a “water economy” with 60 percent of the population directly engaged in agriculture and livestock and 80 percent of Pakistan’s exports based on these sectors. Approximately 97 percent of surface water and almost all sweet groundwater in Pakistan are used in agriculture.

This sector is dominated by large landowners, often absentee landlords, who sit in national and provincial assemblies, have businesses, run and ‘own’ political parties and head ministries and government departments – the ‘powerful’ in this country. They are not inclined towards sharing and developing laws and policies that can result in the manageable allocation of water. While the nation suffers, the powerful and the influential are well-fed, protected and, therefore, not interested in any reform which affects their current comfortable lifestyle. Their apathy is a major cause of heartburn and deprivation for the rest of the populace. Yet as a nation we slumber on.

The government apathy knows no bounds. To this day, the government of Pakistan does not have a national water policy. India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka have had such policies in place for a decade or two to ensure the well-being of their citizens. For the last 15 years, we have been told that the government of Pakistan is working on a water policy. Finally, after much infighting, a draft of the national water policy was presented to the Council of Common Interests a few days ago. But the council could not find the time to discuss it. As a result, we have been water-orphaned again.

The business community and the industrialists have done well in improving the state of our economy. As long as the profits roll in and they can enjoy the perks of commerce, water is not their problem – even though it is going to seriously undermine their commercial practices in the short term. While many organisations espouse corporate social responsibility, when it comes to water, their eyes glaze over, barring a few. Their apathy stems from being in a position to “buy” their way out of problems.

The Pakistani academia is an equal partner in this apathy. It has not done enough to develop water disciplines and has generally not been willing to lead provocative debate and discourse. However, the much-maligned media in Pakistan has played a positive role by frequently highlighting water issues in recent years. But the coverage is largely stilted and uninformed.

So, is this a problem with no ray of hope and way forward? Not so. First, we need to define a course of direction and plan of action that benefits all Pakistanis – whether rich or poor.

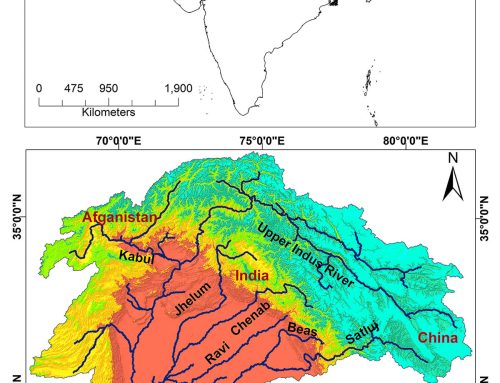

Recently, a voluntary citizens’ body published a set of recommendations as a national water policy framework and prepared over two years of diligent work by leading water experts and society leaders in other disciplines. The solution proposed by the citizens provides a direction and a plan of action, which includes five key focus areas and strategies: improving water access for the poor and landless; financing the water economy and water value chain; safeguarding the Indus Basin and its infrastructure; improving water laws, institutions, governance and management; building a base for science, technology and the social aspects of water. Within these five key areas are 10 goals with a timeframe and measurable results. Most importantly, this water policy provides a starting point for us to avert and manage Pakistan’s water crisis.

While this policy is being disseminated at all levels, including various levels of the government, it has been met with the usual apathy and disinterest. The water crisis cannot afford further neglect and it is time that all stakeholders join hands to make a collective effort to stave off the calamity that is about to befall us.

The writer is the chairperson of Hisaar Foundation.