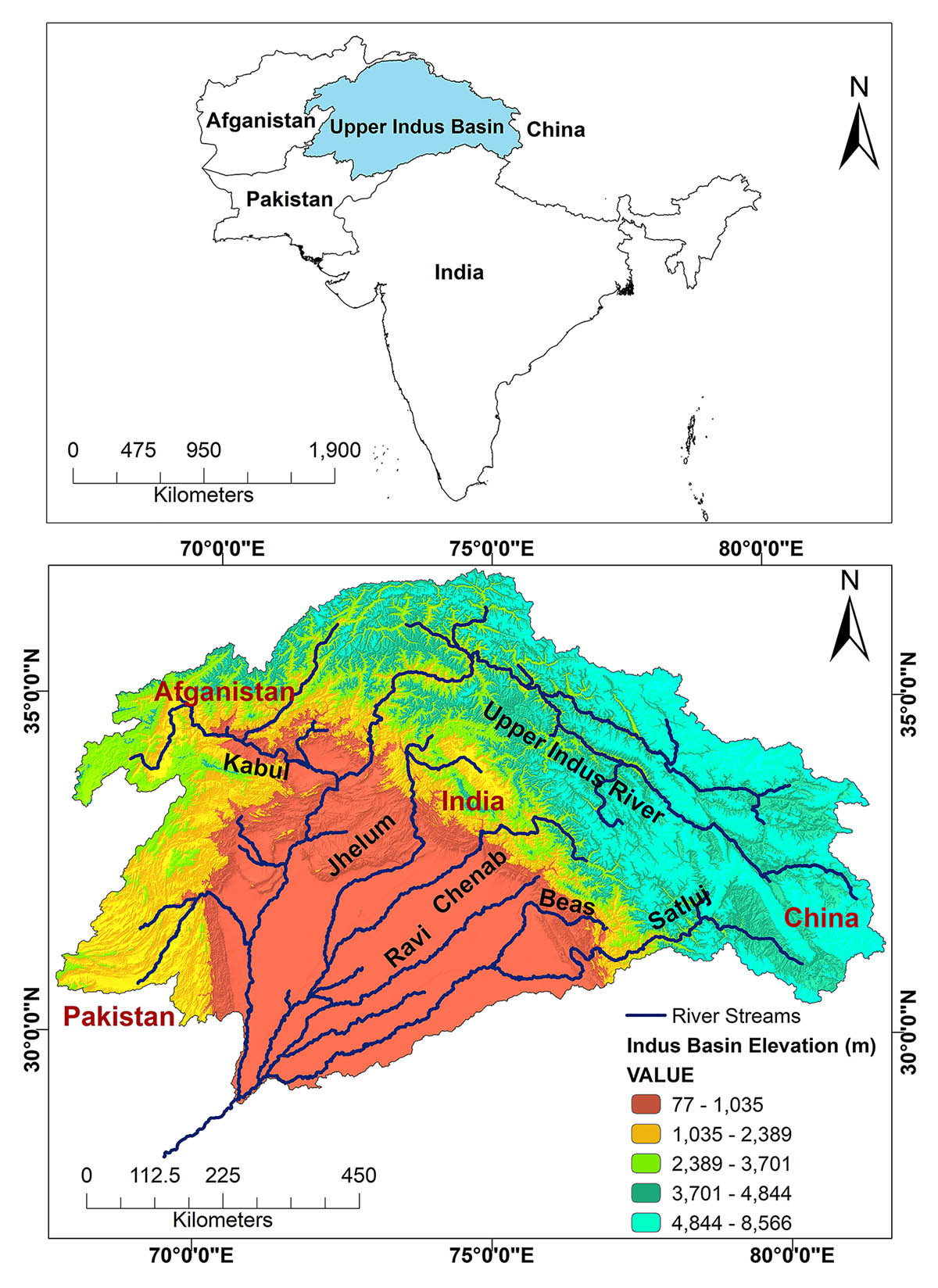

In June 2015, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) ranked Pakistan among the top 36 countries in the world facing an acute water shortage. In January 2018, Cape Town became the first city in the world to say that it was running out of water. The government and citizens went to work together to ward this off and instituted water rationing and water conservation in a massive, collective effort. In Pakistan, it was not until recently that we began to feel the pinch and noticed the signs that had been obvious to water professionals for the last decade — we cannot go on as before; it cannot be business as usual.

The political leadership, in the shape of chief ministers of the federating units of Pakistan, signed a charter for water ‘Pakistan Water Charter’ that demonstrated consensus and political will, and Pakistan’s first National Water Policy (NWP) came out on April 24th, 2018; a triumph indeed for Pakistan, after three decades of dithering. While this National Water Policy is more a wish list with a plethora of goals, it is nonetheless somewhere to begin.

Women remain largely invisible in the water institutions of the country, water-related ministries and department, water NGOs and water businesses. They are seen mostly as ‘affectees’ of the water crisis and climate change and therefore are bracketed as part of the problem.

The National Water Policy needs an implementation framework and that is where we can begin to mainstream the concerns of women. The strength and resilience of women can be harnessed to ward off further crisis, develop rational use of water, improve water management, institute water conservation and achieve water and food security.

Women account for 48.76 per cent of the population of the country, yet they on their own have been referred to only once in the said policy, and that in the context of stakeholder participation in section 18.3 of the policy document where ‘women population will be promoted in domestic water supply and water hygiene.’ This meagre mention shows that in spite of Pakistan’s agriculture-based economy — an economy heavily dependent on water and the work of women — the policy only takes into account women’s participation as domestic users of water.

By several estimates, women provide at least half the agricultural workforce, even if not remunerated or accurately counted. Women in Pakistan are not only careful users of water but also the custodians of water knowledge and practice. They carry the heavy burden of walking several kilometres a day in many parts of rural Pakistan to fetch water for household and livestock use, and continue to face many gender-based discriminatory practices which often determine their access to and their participation in water-related narratives when it comes to claiming entitlements to water. Pakistan’s law does not directly address ‘water rights,’ and land ownership is usually a proxy for access to or entitlement to water. As women in Pakistan own land in a far smaller proportion than their numbers, their ‘water right’ is also limited.

As Pakistan is likely to face a crisis situation in future in terms of water availability due to high population growth rates and the depletion and pollution of its water bodies, it is essential to accept women as a legitimate group to engage with, in efforts to ward off the impending water-related difficulties. Currently, they are not recognised as a party to the current debate in the country on dams, water infrastructure, water distribution, irrigation, agriculture and competing demands for use of water. Very few women are encouraged to pursue education in water-related fields and there are few who have become prominent in this area as visionaries, scientists, planners, managers, technicians, researchers and professionals. The few women engineers and professionals often have challenges at the workplace and social biases due to which their careers and professional advancement opportunities are limited.

Combining Pakistan’s gender equity and equality commitments with water-related goals can give a solid boost to gender mainstreaming in the water sector in Pakistan and ensure that the specific needs and concerns of and impact on men and women from different social and economic groups, are identified and addressed. The new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have the potential to combine and build synergies to put women squarely in the middle of water development, conservation and management. The close inter-linkages of gender, women empowerment and access to water must be reflected in the implementation framework of the Water Policy.

Pakistan must invest in women as drivers of water management and conservation, agricultural growth and food security, and not just as beneficiaries. We have seen Pakistani girls and women bloom in the digital and economic sectors. They can bloom in the water sector too.

Emerging technologies and credit lines in the water sectors can be made more suitable to women’s needs, their knowledge base and their acumen. Emerging agricultural value chains can break down traditional gender divisions of labour. We can design interventions in water supply, irrigation, agriculture and municipal sectors that explicitly target women. There is a need to promote collective action among women and cultivate women’s orientation to income, rather than subsistence-only initiatives — that is, moving from kitchen gardening to productive agriculture and protect women’s control over their economic gains. Such a shift will require more women as service providers, professionals and experts.

Women’s voices need to be mainstreamed into gender inclusive water policy implementation framework. There is still time — we can build equitable measures into the provincial water policies and in the implementation framework of the National Water Policy.